Health Inequalities

What are health inequalities?

Health inequalities are avoidable, unfair and systematic differences in health between different groups of people. There are many kinds of health inequality, and many ways in which the term is used. This means that when we talk about ‘health inequality’, it is useful to be clear on which measure is unequally distributed, and between which people.

Inequalities of what?

Health inequalities are ultimately about differences in the status of people’s health. But the term is also commonly used to refer to differences in the care that people receive and the opportunities that they have to lead healthy lives, both of which can contribute to their health status.

Health inequalities can therefore involve differences in:

- health status, for example, life expectancy and prevalence of health conditions

- access to care, for example, availability of treatments

- quality and experience of care, for example, levels of patient satisfaction

- behavioural risks to health, for example, smoking rates

- wider determinants of health, for example, quality of housing.

Inequalities between who?

Differences in health status and the things that determine it can be experienced by people grouped by a range of factors.

In England, health inequalities are often analysed and addressed by policy across four factors:

- socio-economic factors, for example, income

- geography, for example, region or whether urban or rural

- specific characteristics including those protected in law, such as sex, ethnicity or disability

- socially excluded groups, for example, people experiencing homelessness.

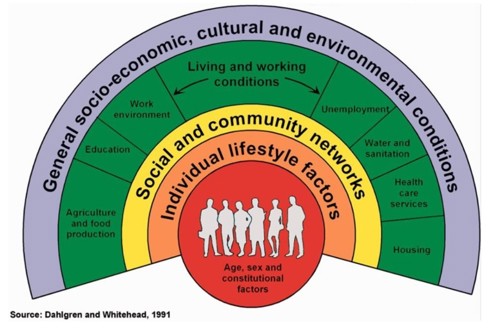

Model of determinants of health ( Dahlgren and Whitehead)

Health Inequalities (Public Health England) (January 2020)

-

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2017 highlights the conditions causing the largest burden (in terms of disability-adjusted life years) in Wirral

-

The purpose of this slide set is to demonstrate inequalities in important high-burden diseases - defined either because they are high burden as measured by the GBD, or because they reflect a national strategic priority

-

This slide set also includes a number of Local Health indicators where there is a particularly strong statistical linear relationship with deprivation as measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019 (IMD 2019) at ward level

-

It uses routinely available data from the Local Health website

-

It uses 2018 ward and local authority boundaries

Health Inequalities (Public Health England) (January 2020)

-

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2017 highlights the conditions causing the largest burden (in terms of disability-adjusted life years) in Wirral

-

The purpose of this slide set is to demonstrate inequalities in important high-burden diseases - defined either because they are high burden as measured by the GBD, or because they reflect a national strategic priority

-

This slide set also includes a number of Local Health indicators where there is a particularly strong statistical linear relationship with deprivation as measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2019 (IMD 2019) at ward level

-

It uses routinely available data from the Local Health website

-

It uses 2018 ward and local authority boundaries

Health Inequalities in Wirral

Local action on health inequalities: evidence papers

This research shows the evidence supporting action to reduce health inequalities.

Introduction to a series of evidence papers

How health inequalities are experienced in England’s population?

People experience different combinations of these factors, which has implications for the health inequalities that they are likely to experience. There are also interactions between the factors. For example, groups with particular protected characteristics can experience health inequalities over and above the general and pervasive relationship between socio-economic status and health.

This explainer from Kings Fund provides an overview of how health inequalities are experienced in England’s population.

Inequalities in life expectancy

Life expectancy is a key measure of a population’s health status. Inequality in life expectancy is therefore one of the foremost measures of health inequality.

Life expectancy is closely related to people’s socio-economic circumstances. The most common summary measure of these circumstances across a population is deprivation. The index of multiple deprivation is a way of summarising how deprived people are within an area, based on a set of factors that includes their levels of income, employment, education and local levels of crime.

In England, there is a systematic relationship between deprivation and life expectancy, known as the social gradient in health. Males living in the least deprived areas can, at birth, expect to live 9.4 years longer than males in the most deprived areas. For females, this gap is 7.4 years.

Importantly, this social gradient relationship holds true across the whole population – health inequalities are experienced by everyone, not just those at the very bottom and top. Figures 1 and 2 show how life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy, which is discussed in the next section, increase as neighbourhood deprivation falls.

This relationship has become known as ‘the Marmot curve’ because of its prominence in Sir Michael Marmot’s report Fair society, healthy lives. Curves showing the same relationship can also be drawn for other measures of deprivation, such as income or education.

Please visit Kings Fund: What are health inequalities?

In recent years, in addition to growth in life expectancy stalling in the population as a whole, inequalities in life expectancy by deprivation have widened. Between 2012–14 and 2015–17, the gap in life expectancy at birth increased by 0.3 years for males and 0.5 years for females. Life expectancy for females in the most deprived areas fell by almost 100 days during this period.

There are also geographical inequalities in life expectancy. The north of England has a higher concentration of deprived neighbourhoods than the south of England, and therefore a greater proportion of communities where life expectancy is likely to be lower. But in addition to this, for any given level of deprivation, life expectancy in the north of England is lower than in the south of England.

The maps below illustrate differences in life expectancy at birth in 2015–17 by local authority areas, using data from Public Health England’s Fingertips tool.

For females, the gap between the area with the lowest life expectancy (Manchester, at 79.5 years) and the area with the highest (Camden, at 86.5 years) is 7 years. For males, the gap is 8.9 years, between Blackpool (74.2 years) and Hart in Hampshire (83.3 years).

Inequalities in healthy life expectancy

Another key measure of health inequality is how much time people spend in good health over the course of their lives, given how crucial good health is to wider quality of life and people’s ability to do the things that they value.

Two important measures of the amount of time that people spend in good health are ‘healthy life expectancy’ and ‘disability-free life expectancy’. The former estimates time spent in ‘good’ or ‘very good’ health, based on how people perceive their general health. The latter estimates, again based on self-reported assessment, time spent without conditions or illnesses that limit people’s ability to carry out day-to-day activities.

Inequalities in both healthy life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy are even wider than inequalities in life expectancy (illustrated by the steeper curves for disability-free life expectancy in Figures 1 and 2). People in more deprived areas spend, on average, a far greater part of their already far shorter lives in poor health.

The gap in healthy life expectancy at birth is stark. In 2015–17, people in the least deprived areas could expect to live roughly 19 more years in good health than those in the most deprived areas. People in the most deprived areas spend around a third of their lives in poor health, twice the proportion spent by those in the least deprived areas.

Again, geographical inequalities exist in this measure. Healthy life expectancy at birth for males in North-East England is 59.5 years, compared to 66.1 years for males in the South East, a gap of 6.6 years. For females, the gap is 5.8 years.

Figures 5 and 6 show healthy life expectancy at birth for males and females in 2015–17 by local authority area. For females, the area with the lowest healthy life expectancy was Nottingham, at 53.5 years, and the area with the highest was Wokingham, at 71.6 years. For males, the area with the lowest healthy life expectancy was Blackpool, at 54.7 years, and the area with the highest was Rutland, at 69.8 years.

Inequalities in avoidable mortality

Some deaths are avoidable through preventive interventions or timely health care. Differences in rates of avoidable mortality between population groups reflect differences in people getting the help that they need to address life-threatening health risks and illnesses.

The Office for National Statistics analyses deaths that could be averted or delayed through timely, effective health care (‘amenable mortality’) or wider public health interventions (‘preventable mortality’). In 2017, more than 140,000 (almost one in four) deaths were considered avoidable according to these definitions. Cancers were the leading cause, followed by cardiovascular diseases, injuries, respiratory diseases and drug misuse.

In England, in 2017, males in the most deprived areas were 4.5 times more likely to die from an avoidable cause than males in the least deprived areas. Females in the most deprived areas were 3.9 times more likely to die from an avoidable cause than those in the least deprived areas.

Figure 7 shows preventable mortality by local authority area between 2016–18. Darker areas have higher rates of preventable mortality. Blackpool had the highest rate at 318.0 per 100,000, more than two and a half times higher than the lowest area, which was Rutland at 118.9 per 100,000.

Inequalities in long-term health conditions

Long-term conditions are one of the major causes of poor quality of life in England. More than 50 per cent of people with a long-term condition see their health as a barrier to the type or amount of work that they can do, rising to more than 80 per cent when someone has three or more conditions. This means that, on top of their direct impact on health status, long-term conditions also have an indirect impact on health, given the importance of being in good-quality work for an individual’s physical and mental health.

People in lower socio-economic groups are more likely to have long-term health conditions, and these conditions tend to be more severe than those experienced by people in higher socio-economic groups. Deprivation also increases the likelihood of having more than one long-term condition at the same time, and on average people in the most deprived fifth of the population develop multiple long-term conditions 10 years earlier than those in the least deprived fifth.

Inequalities in the prevalence of mental ill-health

Assessing differences in the prevalence of mental illness between social groups is challenging and complex, because rates of recognition, reporting and diagnosis are likely to vary between groups. Existing evidence, although in many cases patchy and inconsistent, suggests a number of important patterns.

Evidence suggests that inequalities in various types of mental ill-health exist across a range of protected characteristics, including sexual orientation, sex and ethnicity. People in the United Kingdom who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT), for example, experience higher rates of poor mental health, including depression, anxiety and self-harm, than those who do not identify as LGBT.

The 2014 Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey found that women were more likely than men to report experiencing a common mental health disorder, with one in five women reporting symptoms compared to one in eight men. The gap between women and men was particularly wide among young people, and young women experienced higher rates of reported self-harm and positive screening for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) than men of the same age. Both alcohol and drug dependence were found to be twice as likely in men as in women.

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey also showed some disparities in mental ill-health by ethnicity. For example, rates of psychotic disorder experienced by Black men (3.2 per cent) and Asian men (1.3 per cent) were higher than among White men (0.3 per cent), although for women there was no significant difference by ethnicity. Rates of detention under the Mental Health Act among the ‘Black or Black British’ group were more than four times higher than the ‘White’ group, which has been linked in part to higher rates of serious mental illness. There are also differences in pathways into care (through the police, the criminal justice system or general practitioner contact, for example) for psychosis patients from different ethnic groups.

Several socially excluded groups have been shown to experience higher rates of mental ill-health than the general population. For example, more than 80 per cent of people experiencing homelessness report having a mental health difficulty, and people in this group are 14 times more likely than those in the general population to die by suicide. Asylum seekers and refugees are also at increased risk of experiencing depression, PTSD and other anxiety disorders.

Inequalities in access to and experience of health services

Access to health services refers to the availability of services that are timely, appropriate, sensitive and easy to use. Inequitable access can result in particular groups receiving less care relative to their needs, or more inappropriate or sub-optimal care, than others, which often leads to poorer experiences, outcomes and health status. Access to the full range of services that can have an impact on health includes access to preventive interventions and social services, as well as primary and secondary health care.

Inequitable access might mean that a group faces particular barriers to getting the services that they need, such as real or anticipated discrimination or challenges around language. These issues are often reported for asylum seekers and refugees and Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities. It can mean that information is not communicated in an easily understandable or culturally sensitive way.

We can also measure access in terms of service availability and uptake. More deprived areas tend to have fewer GPs per head and lower rates of admission to elective care than less deprived areas, despite having a higher disease burden.

Different social groups might also have systematically different experiences within the services that they use, including in terms of the quality of care they receive and whether they are treated with dignity and respect. One way of measuring this is in terms of patient satisfaction rates. The 2017 British Social Attitudes survey, for example, found that respondents who identified as Black reported lower levels of satisfaction with the NHS (44 per cent said they were satisfied) than respondents who identified as White (58 per cent). In a recent study by Stonewall, 13 per cent of LGBT respondents reported experiencing unequal treatment from health care staff because they were LGBT, with this number rising to 32 per cent for people who are transgender and 19 per cent for Black, Asian and minority ethnic LGBT people.

Inequalities and young people

Social inequalities can lead to health inequalities. Without equal access to resources and support, some young people are put at a disadvantage and their health may suffer as a result.

Recent publications

Clarifying what we mean by health inequalities for young people

This Association for Young People’s Health (AYPH) briefing paper provides a definition for health inequalities that is specific to young people and a conceptual framework to help us identify causes and levers that influence health outcomes.

Child of the North: building a fairer future after Covid-19

This Northern Health Science Alliance report paints a stark picture of inequality for children growing up in the north of England post-pandemic compared with those in the rest of the country.

It looks at a wide range of factors, from child poverty to children in care, to build up a picture of ‘The Child of the North’. It sets out 18 clear recommendations that can be put in place to tackle the widening gap between the north and the rest of England.

Pathways to health inequalities

The examples above show systematic differences across various measures of health for different population groups in England. This section explores differences in the likelihood of engaging in healthy or unhealthy behaviours and differences in the wider determinants of health, which are important causes of health inequalities arising and persisting over time. Both involve differences in the health risks that people are exposed to and in the opportunities that they have to lead healthy lives.

Inequalities in behavioural risk factors

People’s behaviour is a major determinant of how healthy they are. Public Health England’s 2020–25 strategy identifies smoking, poor diet, physical inactivity and high alcohol consumption as the four principal behavioural risks to people’s health in England today. Behavioural risks to health are more common in some parts of the population than in others. The distribution is patterned by measures of deprivation, income, gender and ethnicity, and risks are concentrated in the most disadvantaged groups. For example, smoking prevalence in the most deprived fifth of the population is 28 per cent, compared to 10 per cent in the least deprived fifth.

Risky health behaviours also tend to cluster together in certain population groups, with individuals in disadvantaged groups more likely to engage in more than one risky behaviour. The prevalence of multiple risky behaviours varies significantly by deprivation. In 2017, the proportion of adults with three or more behavioural risk factors was 27 per cent in the most deprived fifth, compared with 14 per cent in the least deprived fifth.

Health-related behaviours are shaped by cultural, social and material circumstances. For example, recent estimates suggest that households in the bottom fifth of income distribution may need to spend 42 per cent of their income, after housing costs, on food in order to follow Public Health England’s recommended diet.

Furthermore, evidence suggests that some people’s circumstances make it harder for them to move away from unhealthy behaviours, particularly if they are worse off in terms of a range of wider socio-economic factors such as debt, housing or poverty. This is compounded by differences in the environments in which people live, with deprived areas much more likely to have fast food outlets than less deprived areas (Blackpool, for example, has more than five times as many fast food outlets per head than Sevenoaks).

Interventions and services aimed at helping to change behaviours need to be able to adapt to the reality of people’s lives, address the wider circumstances in which behaviours take place, and recognise the difficulty of achieving and maintaining behavioural change under conditions of stress.

The wider determinants of health

- The wider determinants of health are the social, economic and environmental conditions in which people live that have an impact on health. They include income, education, access to green space and healthy food, the work people do and the homes they live in.

It is widely recognised that, taken together, these factors are the principal drivers of how healthy people are, and that inequalities in these factors are a fundamental cause of health inequalities. Addressing these wider socio-economic inequalities is therefore a crucial part of reducing health inequalities.

Table 1 provides some examples of health impacts relating to a range of wider determinants. The examples focus on individual determinants, but these determinants are often experienced together and cumulatively over time. Particular groups can be disadvantaged across a number of factors, and these disadvantages can be mutually reinforcing. Deprived areas have, for example, on average nine times less access to green space, higher concentrations of fast food outlets and more limited availability of affordable healthy food.

Please visit Kings Fund: What are health inequalities?

Interactions between the factors driving health inequalities

Our health is shaped by a complex interaction between many factors. These include the quality of health and care services, individual behaviours, the places and communities in which people live and wider determinants such as education, housing and access to green space. Health inequalities arise as a result of systematic variations in these factors across a population.

Inequalities in these factors are inter-related: disadvantages are concentrated in particular parts of the population and can be mutually reinforcing. Lower socio-economic groups, for example, tend to have a higher prevalence of risky health behaviours, worse access to care and less opportunity to lead healthy lives.

The interactions between different kinds of inequality, and the factors that drive them, is often complex and multidirectional. People can find it more difficult to move away from unhealthy behaviours if they are worse off in terms of a range of wider determinants of health. Access to green space, on the other hand, seems to weaken the relationship between income and health status in a complex way.

Conclusion

Based on factors often outside their direct control, people in England experience systematic, unfair and avoidable differences in their health, the care they receive and the opportunities they have to lead healthy lives.

Interventions to tackle health inequalities need to reflect the complexity of how health inequalities are created and perpetuated, otherwise they could be ineffective or even counterproductive. For example, efforts to tackle inequalities of health status associated with behavioural risks (such as poor diets) should address the wider network of factors that influence these behaviours (such as access to affordable healthy food, marketing and advertising regulations) and the impact that these behaviours have on health outcomes (such as access to clinical services).

Health inequalities are not inevitable and the gaps are not fixed. Evidence shows that a comprehensive approach to tackling them can make a difference. Concerted, systematic action is needed across multiple fronts to address the causes of health inequalities. This includes, but goes well beyond, the health and care system.

Kings Fund will continue to provide more on health inequalities in the near future.

Please visit Kings Fund: What are health inequalities?

We have produced and/or published a range of content over the years that can be seen below.

Previous Content

Previous section

Download Health Inequalities Chapter (Warning large document) (Last refreshed October 2012)

Evidence

The disease of disparity: a blueprint to make progress on health inequalities in England (October 2021)

This Institute for Public Policy Research report identifies six areas where policy needs to change to tackle health inequality, and makes recommendations across the NHS and the socio-economic drivers of poor health. Combined, these provide a constructive plan to tackle the ‘disease of disparity’ in England – and to achieve the health, social and economic gains possible from addressing health inequality.

Moving out to move on Understanding the link between migration, disadvantage and social mobility (July 2020)

This report by the Social Mobility Commission looks at the reasons people may choose to move from one area to another. The report shows that those who move to London and the south-east still have much better job prospects, and earn higher pay than those who stay in their areas irrespective of their background. ‘Movers’ will on average earn 33% more than ‘stayers’ and are 50% more likely to have a degree. They typically move whilst in their 20s – often gravitating towards London and the south-east – and are more likely to end up in managerial or professional jobs, says the research.

Due North: Inquiry on Health Equity for the North (September 2014)

There has been a North-South health divide in England for a long time now, with the gap continuing to widen over the past four decades. The causes of health inequality are broadly similar across the country and on average, poor health increases with increasing socioeconomic disadvantage. But the severity of these causes is greater in the North. Further, austerity measures are making the situation even worse, impacting more heavily on the North and disadvantaged areas. It is against this background that the independent Inquiry on Health Equity for the North was set up. The report, Due North, details evidence on trends in health inequalities and a set of recommendations. It has sought to bring a fresh perspective to the issue of health inequalities, seeking to build upon the assets of the North to target inequalities, whilst also outlining what central government needs to do, both to support action at the regional level and re-orientate national policies to reduce inequalities.

View the Executive Summary or for the full report

Health Inequalities: Marmot Review 10 Years On

Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On

UK life expectancy has been stalling at the same time as a decade of austerity. The 10 Years On Review, #Marmot 2020, will confirm a widening of health inequalities, a widening of health inequalities and set out the current cost to society of avoidable health inequalities (health inequities).

In the ten years since the publication of The Marmot Review, health inequalities appear to be widening, and life expectancy increases have stalled. The country urgently needs to reprioritise and take action on health inequalities.

The report highlights that:

-

people can expect to spend more of their lives in poor health

-

improvements to life expectancy have stalled, and declined for the poorest 10% of women

-

the health gap has grown between wealthy and deprived areas

-

place matters – living in a deprived area of the North East is worse for your health than living in a similarly deprived area in London, to the extent that life expectancy is nearly five years less.

Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years On, was published in February 2020

Marmot and Health Inequalities: Indicators for Local Authorities in England

Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot Review report was published in February 2010, presenting the recommendations of the Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010. In February 2011, the first Marmot Indicators for local authorities were released, providing information to support monitoring of the overall strategic direction in reducing health inequalities. These indicators were updated in 2012.

Then launched in September 2014 by the Institute of Health Equity, the Marmot Indicators 2014 were developed in collaboration with Public Health England.

They are a new set of indicators of the social determinants of health, health outcomes and social inequality, that broadly correspond to the policy recommendations proposed in Fair Society, Healthy Lives.

These 2014 indicators can be accessed below in a spine chart format, which displays data for the following:

-

Healthy life expectancy at birth – males and females

-

Life expectancy at birth – males and females

-

Inequality in life expectancy at birth – males and females

-

People reporting low life satisfaction

-

Good level of development at age 5

-

Good level of development at age 5 with free school meal status

-

GCSE achieved (5A*-C including English & Maths)

-

GCSE achieved (5A*-C including English & Maths) with free school meal status

-

19-24 year olds who are not in employment, education or training

-

Unemployment % (ONS model-based method)

-

Long-term claimants of Jobseeker's Allowance

-

Work-related illness

-

Households not reaching Minimum Income Standard

-

Fuel poverty for high fuel cost households

-

Percentage of people using outdoor places for exercise/health reasons

There are a number of key issues facing Wirral residents based upon the analysis in this report and in addition are likely to be felt more acutely in areas of the borough facing greatest disadvantage. To rebalance these outcomes a number of initiatives are in place and being developed to mitigate impacts and reduce future incidence.

No new updates have been produced

Wirral's 2014 report

There are a number of key issues facing Wirral residents based upon the analysis in this report and in addition are likely to be felt more acutely in areas of the borough facing greatest disadvantage. To rebalance these outcomes a number of initiatives are in place and being developed to mitigate impacts and reduce future incidence.